A recent Psychology Today blog post argues that the quality of the therapist–client relationship matters far more than any specific therapeutic approach or “brand” of therapy. It suggests that “decades of research” show most evidence-based therapies are equally effective, implying that the modality is almost irrelevant. The author contends that strong relationships are what make therapy effective, while terms like “evidence-based” or specific models (CBT, DBT, etc.) are mostly marketing hype. This perspective, however, oversimplifies a complex issue. Yes, the therapeutic alliance is crucial, but it’s not the only factor in successful therapy. In reality, effective therapy is a combination of a strong relationship and the right evidence-based techniques for the problem at hand. Misrepresenting the evidence can do more harm than good for those seeking help in a confusing mental health marketplace.

In this article, we’ll “check the facts” (to borrow a Dialectical Behavior Therapy skill) and examine what research actually shows about therapeutic relationships versus treatment modalities. We’ll highlight data on when specific therapy approaches make a difference, using Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) as a case in point. We’ll also discuss the role of therapy “brands” and why identifying as evidence-based is more than just marketing. The goal is a clearer, more nuanced understanding: the therapeutic relationship does matter greatly, and so do evidence-based interventions.

Therapeutic Alliance: Crucial, But Only Part of the Equation

There’s no doubt that a strong therapeutic alliance – trust, empathy, and collaboration between client and therapist – is one of the best predictors of positive outcomes in therapy. Decades of studies back this up. In fact, meta-analyses find that the quality of the therapist–client relationship accounts for a significant portion of the variance in therapy outcomes – roughly 15% of outcome variance in adult psychotherapy by some estimates. This makes the alliance one of the largest single factors linked to success. Clients who feel understood and supported tend to have better engagement and more improvement.

However, saying “relationships are what make therapy effective” as if that’s the whole story is misleading. The research “story” is more complex. Therapy outcome is determined by multiple factors. Besides the alliance, other common factors like client motivation and expectations also contribute. Notably, the specific therapeutic methods and techniques used – the “active ingredients” of therapy – also play an important role (even if a somewhat smaller one overall). Estimates suggest that the specific treatment approach may account for around 5–10% (or more) of outcome variance on average. That might sound modest, but it can be a meaningful difference, especially for certain disorders and in aggregate across many patients.

Crucially, these percentages are averages and don’t mean that any warm relationship will produce the same results as a skilled therapy that also applies effective techniques. The therapeutic alliance is necessary but not always sufficient for recovery. A strong bond can increase a client’s hope and willingness to engage, but without appropriate interventions, some conditions won’t fully remit. To use an analogy: in medicine, having a caring doctor is very important for healing, but if you have an infection you likely also need the right antibiotic to actually cure it. Similarly, a great therapist who only provides support may not help an obsessive-compulsive disorder nearly as much as a therapist who provides support and guides the client through Exposure and Response Prevention (the evidence-based treatment for OCD).

Research bears this out. Studies show that the most effective therapy outcomes typically occur when a strong alliance is paired with techniques targeted to the client’s problems. One review concluded that “psychotherapy is effective when it incorporates three pathways: a real therapeutic bond, fostering hopeful expectations, and therapy-specific techniques that facilitate change”. In other words, it’s not relationship versus technique – the best results come from integrating both. A warm, trusting relationship lays the foundation (providing safety, empathy, and motivation), and evidence-based methods provide the structure and tools for change.

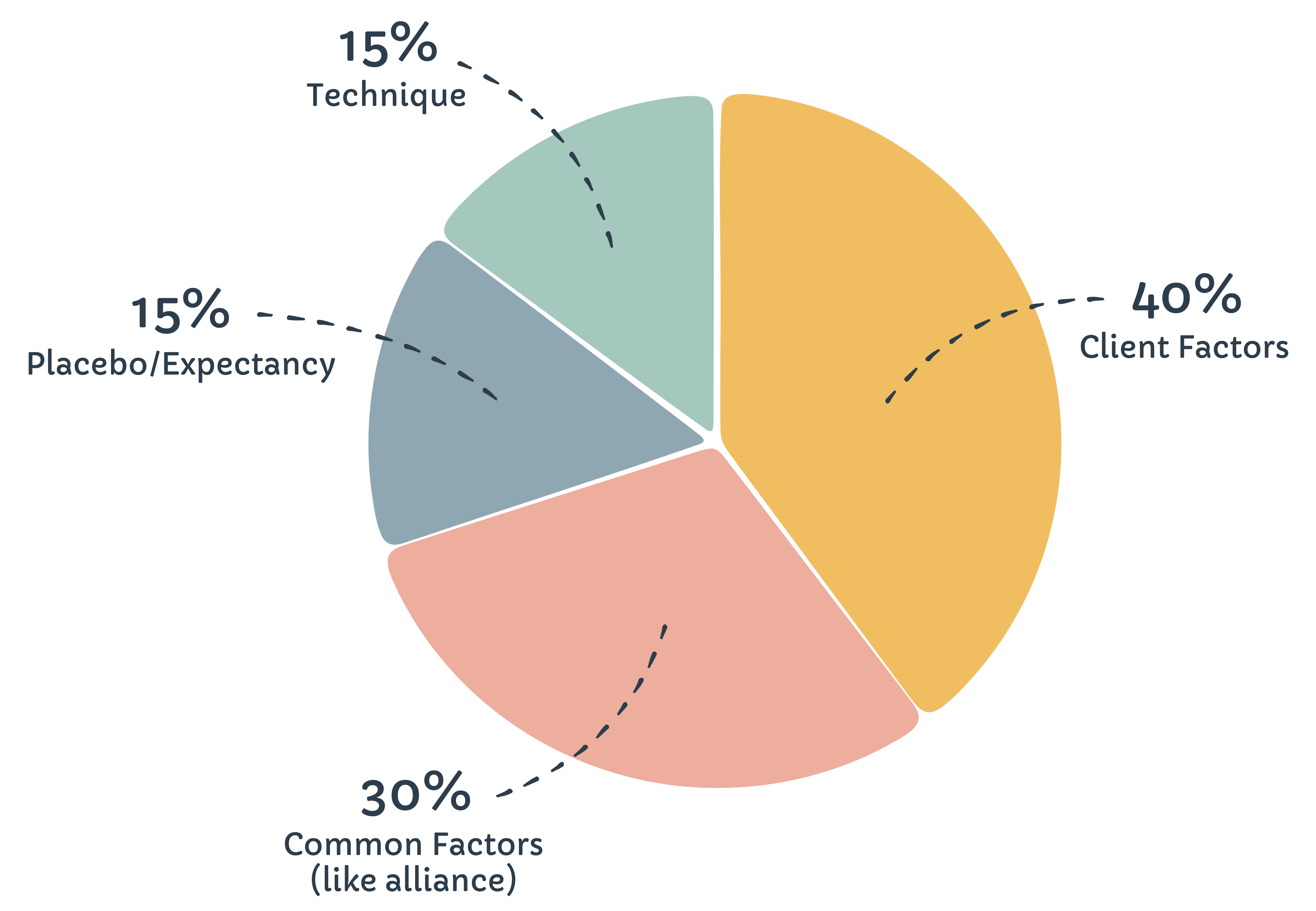

To put the alliance in context, consider that even the most supportive therapist cannot simply talk a phobia away without some form of exposure to the feared object. Conversely, a rigid technician who ignores the human relationship may fail because the client doesn’t engage. As psychologist Clark and colleagues famously estimated, outcome in therapy is roughly 40% due to client factors, 30% common factors (like alliance), 15% placebo/expectancy, and 15% technique – a rough heuristic often cited in literature. While the exact percentages are debated, the clear point is that relationships matter a lot, but they are not everything.

Are All Evidence-Based Therapies Equally Effective? A Closer Look

The blog author asserts that “decades of research suggest that most evidence-based therapies are similarly effective” – essentially the “Dodo bird verdict” that “everybody has won and all must have prizes.” It’s true that this has been a prominent viewpoint in psychotherapy research. Much of this comes from work by researchers like Bruce Wampold, who argue that when bona fide therapies are compared in clinical trials, differences in outcomes are often small to nonexistent. For example, a comprehensive analysis by Wampold and colleagues found that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) had outcomes comparable to psychodynamic or humanistic therapy on average. Similarly, a large review of over 100 studies of depression treatments found no one therapy was significantly more effective than others – at least not by the modestly powered trials available. This is the basis for the claim of “mostly equal” outcomes.

However, there are important nuances and caveats here. First, many of those comparative studies lacked the statistical power to detect anything but fairly large differences. Small but meaningful advantages of one treatment could be missed. When researchers do aggregate meta-analyses or look at specific conditions, some differences do emerge. For instance, psychologist David Tolin conducted a meta-analytic review asking if CBT is more effective than other therapies. He found that for anxiety and depressive disorders, CBT was indeed superior to at least one major alternative (psychodynamic therapy), both at post-treatment and follow-up. (CBT performed similarly to another structured approach, interpersonal therapy, in that analysis.) Tolin concluded that these results “argue against [the] claim of treatment equivalence” and suggested CBT should be a first-line treatment for those common disorders. In other words, when you zoom in on certain diagnoses, the type of therapy can make a significant difference in outcomes.

Moreover, not all “evidence-based therapies” have equally strong evidence! The blog lumps together CBT, DBT, Internal Family Systems (IFS), Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), EMDR, etc. as if they’re the same tier. In reality, the research base for these varies. CBT is backed by thousands of studies across conditions. Dialectical Behavior Therapy has dozens of clinical trials supporting its efficacy for borderline personality disorder and related problems. EMDR has a solid evidence base for trauma. Internal Family Systems, on the other hand, is an emerging approach with promising but still preliminary research. As the blog itself notes, IFS interest is growing and some initial studies are positive, but it doesn’t yet have the volume of evidence of older modalities. For example, a small recent pilot study of an IFS-based program for PTSD found it feasible and associated with PTSD symptom reduction in about half of participants, which is encouraging. But such early findings need to be replicated in larger trials before we can equate IFS’s efficacy to, say, prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Not all brands under the “evidence-based” umbrella are equally proven. Grouping therapies with very different research support under one umbrella of “all effective” obscures these distinctions.

Crucially, some specific therapies show significant efficacy for particular problems, outperforming others, and this gets lost in an overgeneralized “all are equal” message. Take specific phobias: a robust body of evidence shows that exposure therapy (gradually and systematically facing fears) is extraordinarily effective, with success rates often quoted around 60–90% for significant improvement or remission. One clinical fact sheet notes that “studies show that exposure therapy helps over 90% of people with a specific phobia who commit to the therapy and complete it”. Ninety percent! Clearly, in this case, the technique (exposure) is critical – a phobic patient isn’t likely to achieve that outcome through supportive listening alone. Likewise, for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma-focused therapies (such as prolonged exposure or cognitive processing therapy) have consistently outperformed non-trauma-focused approaches in reducing PTSD symptoms. Clinical guidelines strongly recommend these trauma-focused modalities as first-line treatments. In contrast, generic supportive counseling or psychodynamic therapy (without directly addressing the trauma) tend to be less effective for PTSD – and guidelines like NICE (UK) specifically advise against those as first-line care in favor of evidence-based trauma-focused interventions. These examples illustrate that the type of therapy does matter a great deal in many scenarios. Claiming otherwise can mislead consumers.

Even the blog’s own examples hint at this nuance. The author mentions that Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples has strong outcomes but in studies performs about as well as other structured couples therapies. That doesn’t mean “anything goes” in couples work – it means several structured, evidence-based approaches all work, likely because they share common effective elements (e.g. improving communication and emotional responsiveness). But an unstructured, non-evidence-based couples intervention likely wouldn’t match those outcomes. In other words, grouping effective therapies together is not the same as saying any arbitrary approach will yield equal results. The real takeaway is that many bona fide therapies have efficacy, but one still must choose the right type of bona fide therapy for the situation.

In sum, the oft-cited notion that “most therapies are equal” comes with important reservations. When researchers have enough data and dissect by condition, winners and losers do emerge for certain disorders. Some therapies simply fit a given problem better. Dismissing the value of specific modalities entirely overlooks these critical differences. It’s more accurate to say common factors (like alliance) are powerful across all therapies, and specific factors (techniques) make a meaningful difference, especially in treating particular diagnoses. The art of good therapy is integrating both: harnessing common factors and delivering the right specific interventions.

DBT in Focus: A Case Study of Modalities Making a Difference

To illustrate how a therapeutic “brand” with strong evidence can offer unique benefits, let’s look at Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) – the approach our organization (TheraHive) specializes in. The blog’s author actually knows DBT well (she’s written a DBT workbook) and acknowledges that “DBT is effective in treating borderline personality disorder (BPD) and chronic suicidal thoughts”. But the article implies DBT is just one of many branded methods, no better or worse than others except for marketing. In reality, DBT’s development and track record demonstrate the value of a specialized, evidence-based modality – one that combines a strong relationship with concrete skills and strategies.

What is DBT? It was developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan specifically for clients with BPD and severe self-harm or suicidal behavior, a group for whom traditional therapies often failed. Standard CBT at the time, focused on changing thoughts and behaviors, wasn’t sufficient – clients felt invalidated and many dropped out. Linehan’s innovation was to integrate acceptance, validation, and mindfulness (drawing from Zen practices) with behavioral change techniques. She emphasized building a strong, compassionate therapist–client relationship (acceptance) and teaching coping skills to manage emotions, tolerate distress, and navigate relationships (change). This balance is even reflected in the name “dialectical” – synthesizing acceptance and change.

Does DBT work? The evidence says yes. DBT was the first psychotherapy proven effective for BPD in controlled trials. Numerous studies have found that comprehensive DBT significantly reduces suicidality, self-harm, and psychiatric hospitalizations compared to treatment-as-usual. For example, in one landmark randomized trial, patients receiving DBT had about half the suicide attempt rate of those receiving expert-standard therapy over a two-year period, along with significantly fewer emergency room visits and inpatient admissions. Notably, DBT also kept patients in therapy longer – it has lower dropout rates than comparison treatments with this challenging population. These outcomes are not just due to “having a therapy” or a good alliance in general; they reflect the impact of DBT’s specific package: weekly individual therapy, group skills training, phone coaching for crises, and a therapist consultation team to support providers. In other words, the DBT approach, as a modality, has unique elements that produce better results for high-risk clients. A recent meta-analysis of 18 trials confirmed that DBT effectively reduces self-injurious behaviors and use of emergency services in individuals with BPD, with large pre–post improvements noted.

Importantly, DBT doesn’t achieve these outcomes by ignoring the therapeutic relationship – quite the opposite. It places heavy emphasis on the alliance. Therapists practice validation strategies to ensure the client feels heard and respected, and the therapy itself is structured in stages to first get agreement on goals and build trust. In fact, one reason DBT is theorized to have lower dropout is because clients finally feel understood (their extreme emotions are validated as understandable) while still being held accountable to change. This shows how modality and relationship work hand in hand. DBT formalizes both: it has relationship-building strategies and evidence-based techniques. The result is that many clients who previously felt “therapy doesn’t work for me” or who were stuck in a revolving door of ER visits found stability through DBT.

DBT has now been adapted for many other hard-to-treat conditions – from substance use disorders to eating disorders to adolescents engaging in self-harm – and research is accumulating there as well. For instance, adaptations of DBT have shown promise in reducing suicide attempts in adolescents with bipolar disorder and in improving emotion regulation in teens with self-harm behaviordepts.washington.edu. While more research is ongoing, the principles of DBT (skills training in mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, combined with a validating therapy relationship) are helping fill gaps where purely supportive therapy often fell short.

The take-home point is that DBT as a modality brings something extra. It’s not just a generic therapy with a fancy label; it’s a specific, multi-component treatment born from scientific testing and iteration. Clients often know what they’re getting with DBT: a structured program with concrete skills to practice, coaching between sessions if needed, and a therapist who will both accept them as they are and push them to grow. For many struggling individuals, that “brand promise” (in marketing terms) is life-changing. This is why we at TheraHive center our services on delivering high-quality DBT skills education – because the evidence supports its efficacy and we want clients to reliably get those benefits.

The Role of “Brands” and Evidence-Based Signals in Therapy

The blog writer cautions that therapy has become too focused on “buzzwords and branding,” implying that terms like “evidence-based” or specific model names are mostly marketing noise. It’s true that marketing can sometimes oversell or oversimplify therapy. We’ve all seen therapist directories or social media posts littered with trendy labels (CBT, trauma-informed, attachment-based, etc.) that prospective clients might not fully understand. And certainly no one should choose a therapist solely because they advertise a particular brand or claim – the personal fit and competence matter most. But dismissing “brands” outright misses their important function for consumers of mental health services.

In the marketplace of therapy, a brand is basically a promise. Whether it’s a company (like BetterHelp or Talkspace) or a modality (like EMDR or DBT), a brand tells the consumer something about what they will get. For example, BetterHelp and Talkspace advertise convenient online therapy; their “brand promise” is accessibility. Likewise, if a therapist or clinic brands itself as providing “dialectical behavior therapy”, that signals to clients that they will receive a structured, skills-focused treatment approach originally designed for severe emotion dysregulation. That’s useful information. It sets expectations and helps clients make informed choices. Someone who knows they want to learn practical coping skills might actively seek out a DBT program – and when they see the TheraHive brand, which emphasizes high-quality DBT skills education, they know this aligns with their needs.

Moreover, when therapists describe themselves as “evidence-based”, this is more than just a buzzword – it’s a professional value statement. According to the American Psychological Association, evidence-based practice means “integrating the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics and preferences.” In plain language, an evidence-based therapist stays up-to-date on scientific findings, uses proven techniques, measures outcomes, and tailors therapy to the individual. That should reassure clients: it means the clinician isn’t just winging it with personal theories but is grounded in approaches that have been tested in clinical research. In contrast, a therapist who doesn’t claim any evidence-based orientation might be using unproven methods or sticking only to what they learned decades ago in school. While experience and intuition are valuable, ignoring scientific progress is not a virtue in healthcare. When navigating the crowded therapy marketplace, seeing terms like CBT, DBT, EMDR, or “evidence-based treatment” can help clients identify therapists who align with a scientific, results-oriented approach to care. It’s a positive signal, not just hype – provided the therapist truly has training in that approach.

Of course, the concern (which the blog rightly touches on) is that sometimes these labels can be misused as marketing – a therapist might list every modality under the sun, or a clinic might advertise “trauma-informed” while providing mediocre services. This is why consumers should ask questions and seek details (e.g. “What does being evidence-based mean in your practice? How do you incorporate DBT skills?”). But the solution is not to throw out the concept of brands or evidence-based labels altogether. Rather, we should protect those terms and use them meaningfully. Just as in medicine you’d want to know if a provider uses evidence-based treatments for, say, diabetes, it’s entirely reasonable to seek a therapist who offers evidence-based therapy for your condition.

Brands in therapy also help standardize quality to some degree. If you sign up for a certified DBT program, you can expect certain components (skills groups, phone coaching, etc.) – it’s not a grab-bag; it’s a known model with standards. This reduces the variability in what “therapy” might entail. For a consumer, that consistency is valuable. It means less guesswork about what you’re signing up for. In a field as varied as mental health, reputable brands and models provide an anchor of reliability.

Finally, let’s address the blog’s parting shot: “Real therapy isn’t a brand. It’s a relationship.” This catchy line sets up a false dichotomy. Real therapy is a relationship and, often, it’s delivered through a framework or approach – sometimes a branded, evidence-based one. A strong therapeutic relationship can form in any modality (CBT, psychodynamic, you name it) if the therapist is skilled. And conversely, an evidence-based modality delivered without a genuine relationship will likely falter (imagine a DBT therapist who rigidly runs through skills but is cold or judgmental – few clients would benefit). The ideal is to have both: a trusting relationship and a solid framework grounded in evidence. These elements are complementary, not mutually exclusive.

Conclusion: Integrating Relationship and Evidence for Best Outcomes

Navigating the mental health landscape is challenging enough for people seeking help – and oversimplified claims like “it’s the relationship that heals, nothing else really matters” do a disservice. They risk misleading clients into thinking they need not consider what type of therapy or what skills their therapist offers. In reality, as we’ve seen, the nature of the treatment approach can greatly affect outcomes. While a good bond is essential in any therapy, certain disorders require specific strategies to overcome. Ignoring that fact could delay someone’s recovery or lead them to abandon therapy thinking it “didn’t work” – when perhaps they just hadn’t found the right approach yet.

On the other hand, the blog’s caution against overreliance on buzzwords carries a kernel of truth: We shouldn’t reduce therapy to a set of technical ingredients and forget the human connection. The common factors – empathy, trust, collaboration, hope – are the soil in which any therapeutic technique must be planted to grow. A mediocre therapist following a manual by rote won’t get great results, because therapy is more than a formula. It’s an art and a science. The best outcomes occur when a therapist can form a strong alliance and deliver empirically supported techniques tailored to the client As one set of researchers put it, effective therapy involves “the patient–therapist bond, fostering hope and expectancy, and therapy-specific techniques that facilitate change”. We should strive to not “forget what truly matters”, but rather recognize all that matters in therapy – both the relationship and the interventions.

In summary, research supports a balanced view: The quality of the therapeutic relationship is a robust predictor of improvement, and choosing an appropriate evidence-based modality markedly boosts the chances of success in many cases. Instead of pitting these factors against each other, we should help clients understand how they work together. An evidence-based, relational therapist will focus on you – building trust and understanding your unique context – and will also bring the wisdom of clinical science to guide treatment. That combination of heart and science is what makes therapy most effective.

Bottom line: Don’t fall for a false choice between finding a caring therapist and finding the “right” therapy – you deserve (and can have) both. Seek out a therapist who makes you feel safe and heard, and pay attention to the methods they use and their grounding in research. The relationship might be what initially engages and supports you, but the targeted skills and insights from an evidence-based modality are often what empower you to heal and change in the long run. By embracing both the relationship and the science, therapy can fulfill its true potential to help people thrive.

Sources:

- Petracek, L. (2025). It’s the Relationship That Matters Most in Therapy. Psychology Today. (“The Psyche Pulse” blog) psychologytoday.compsychologytoday.com.

- Cuijpers, P. (2016). Are all psychotherapies equally effective in the treatment of adult depression? Journal of Psychiatry. (Finding that small sample sizes make it hard to detect modest differences, contributing to the “equal outcomes” view) pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Tolin, D. (2010). Is cognitive-behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies? A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 710–720. (Finding CBT superior to psychodynamic therapy for anxiety/depression in bona fide comparisons)pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Cleveland Clinic (2023). Exposure Therapy. (Noting that exposure therapy can help >90% of people with specific phobias who complete treatment)my.clevelandclinic.org.

- Schwartzkopff, L. et al. (2021). Which trauma treatment suits me? Frontiers in Psychology, 12:694038. (Noting trauma-focused therapies are most effective for PTSD; guidelines recommend PE, CBT, EMDR as first-line)frontiersin.orgfrontiersin.org.

- PTSD UK (2023). IFS research update. (Reporting a pilot study where an IFS-based program for PTSD led to clinically significant PTSD symptom reductions in about 53% of participants, reflecting emerging evidence for IFS)ptsduk.org.

- Roemer’s Therapy blog (2023). Evidence-Based Approach in Psychotherapy: Why is it important?. (Summarizing that evidence-based modalities like DBT show significant benefits; DBT meta-analyses show reduced suicidality and self-harm)roamerstherapy.comroamerstherapy.com.

- Zeyrek, Ç. et al. (2020). Dialectical Behavior Therapy in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. CBT & Research Journal, 9(2), 148–157. (Reviewing DBT components; citing Linehan et al. trials where DBT halved suicide attempts and ER visits vs. expert treatment, and reduced dropout)jcbpr.orgjcbpr.org.

- Norcross, J. & Lambert, M. (2019). Psychotherapy Relationships That Work (3rd ed.). (Comprehensive review of how various relationship factors correlate with outcomes; notes alliance accounts for around 15% of outcome variance)frontiersin.org.

APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285. (Defines evidence-based practice as integrating best research with clinical expertise and patient needs)roamerstherapy.com.

{{promo-banner-1}}

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)